Unless you’ve been making your coffee from under a rock lately, you probably heard that scientists recently caught up with something home baristas have known for nearly two decades: that spraying your coffee with water just before grinding can reduce the amount of static created while grinding. Less static means less chaff stuck to every surface, less coffee stuck in your grinder, and, most importantly of all, fewer clumps in your grinds. According to the researchers, this can boost the extraction in your espresso — but the effect seems to depend on your coffee, and perhaps also on your grinder.

Static makes coffee stick to grinders and form clumps. The finer the grind, the more static is created.

The new research comes from a team led by Christopher Hendon, the computational chemist who also helped introduce baristas to freezing their coffee beans, adding magnesium to their water, and most recently the art of Turbo Shots. He teamed up with, believe it or not, some volcanologists, who study the effects of static in volcanic eruptions and found some interesting parallels to the way coffee creates static during grinding. The paper is free to read for anyone, so check it out here.

A Quick Spritz Zaps Static

The trick of spraying water on coffee before grinding it is generally called the ‘Ross Droplet Technique’ (RDT), after one David Ross who supposedly originated the idea on a coffee forum sometime in 2005. For many years — much like the Weiss Distribution Technique — the RDT was popular with home baristas but rarely seen on bar.

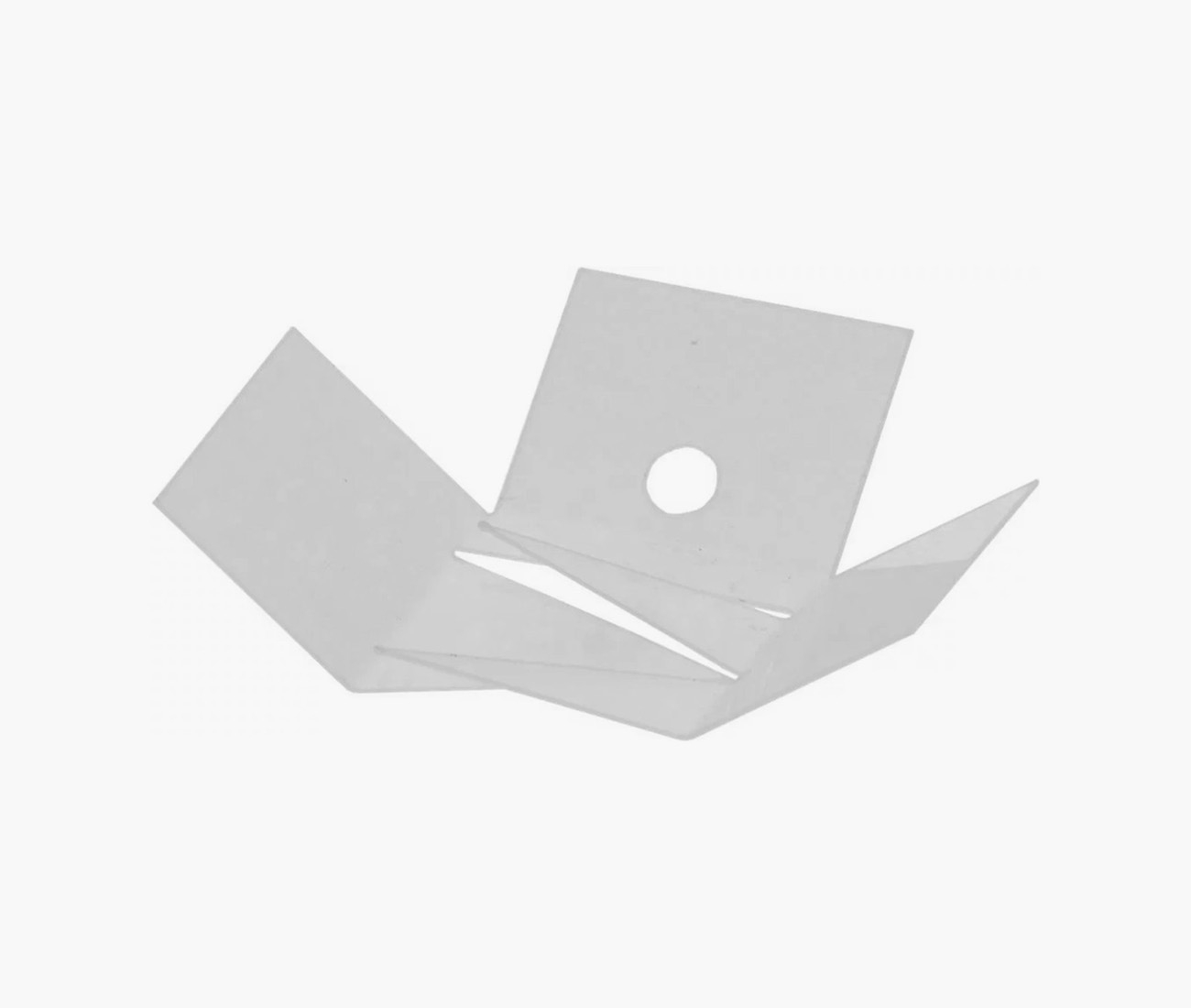

Baristas with commercial equipment rarely worried too much about static and clumping. Espresso grinders came fitted with tools such like Victoria Arduino’s ‘clump crushers’ to break up clumps anyway, and the idea of adding an extra 30 seconds to your workflow to spritz your coffee beans with water, grind a single dose at a time, stir the grounds with a needle tool, and level the coffee off with a special tool before tamping, was unthinkable to a professional barista.

Espresso grinders employ various techniques to reduce the effects of static, such as Victoria Arduino’s ‘clump crushers’ (left) or Mazzer’s grid screen (right).

How times have changed. As single-dose grinding has become more popular, and baristas have used esoteric methods to chase higher and higher extractions, techniques like the RDT and WDT are suddenly everywhere. Not to mention our very own AutoComb, which builds on the idea of the WDT and makes the process of declumping coffee grounds as quick and consistent as possible.

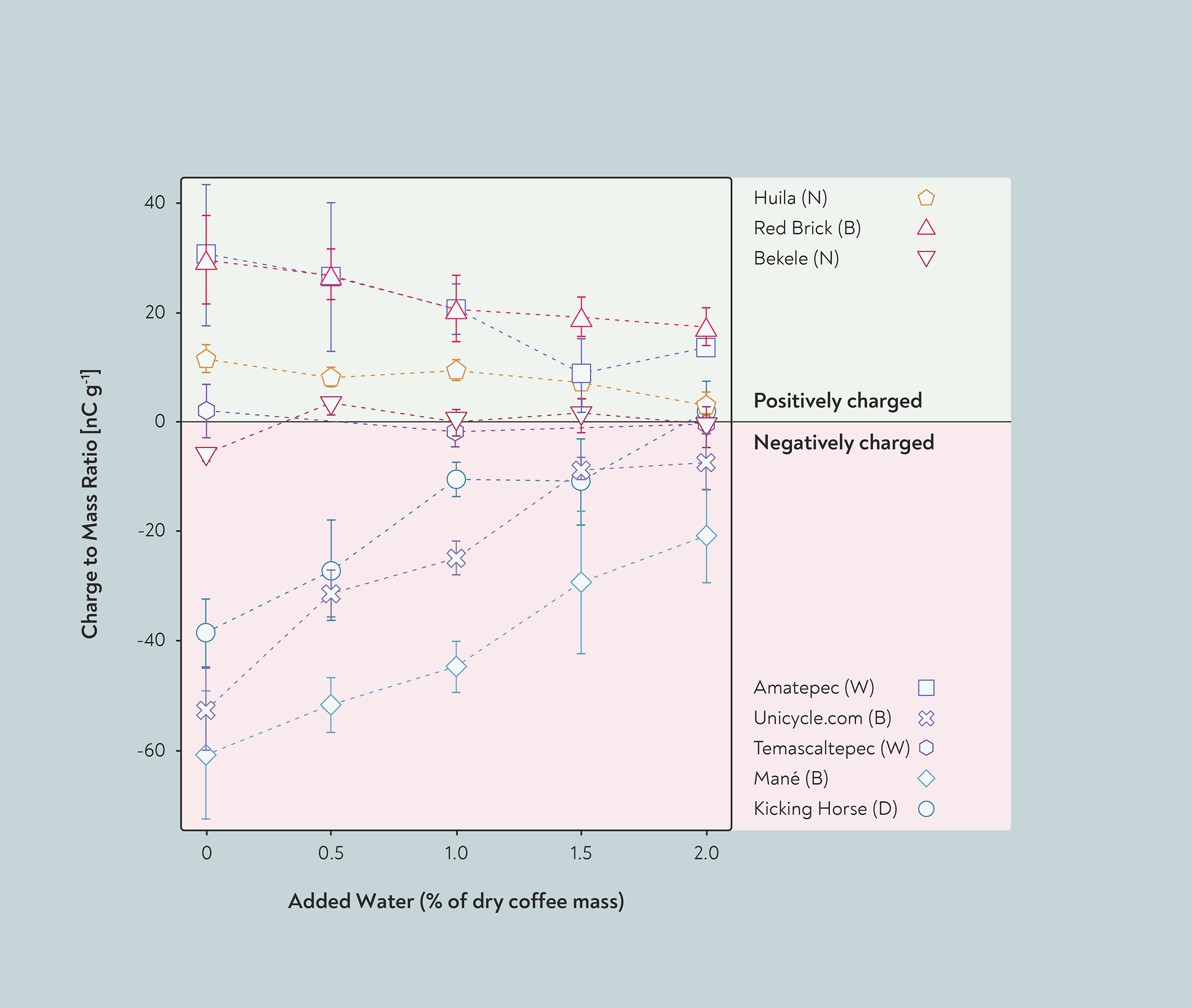

But while the RDT might not be new, the science behind it is. What Hendon discovered is that the static generated during grinding isn’t uniform. Some coffees generate more static than others, and particles may be positively charged, negatively charged, or even a mix of both. Darker roasts tend to generate stronger negative charges — and fines in particular seem to pick up more negative charge. On the other hand, lighter roasts and larger particles of any roast style, are more likely to be positively charged.

The static causes the negatively charged fines to stick to larger particles, creating small (1–2mm) clumps that act as single large particles. These clumps, the theory goes, act like boulders — they reduce the surface area of the coffee available to the water, and create uneven flow through the coffee bed, reducing extraction.

Static causes fines to bind to larger particles, creating small clumps 1–2mm in size.

Static causes fines to bind to larger particles, creating small clumps 1–2mm in size.

Adding water neutralises static and prevents these small clumps from forming. To get the biggest reduction in static charge, the researchers found, you need to add up to 2% of the weight of the coffee in water — much more than the single spritz that many baristas use. When they did this before making an espresso, Hendon’s team found that the shots ran much more slowly — taking up to 50% longer. At the same time, their extraction in those shots increased by approximately 10%.

Crushing Clumps with the AutoComb

So where does the AutoComb fit into this story? Well, the purpose of the AutoComb is to break up clumps. We wanted to know if the AutoComb was working in a similar way to the RDT, and if so, which technique worked better — so we set out to compare the two.

The AutoComb on the world stage: Chris Sotiros, the Swiss Barista Champion, preps his puck at WBC 2023 in Athens.

The AutoComb on the world stage: Chris Sotiros, the Swiss Barista Champion, preps his puck at WBC 2023 in Athens.

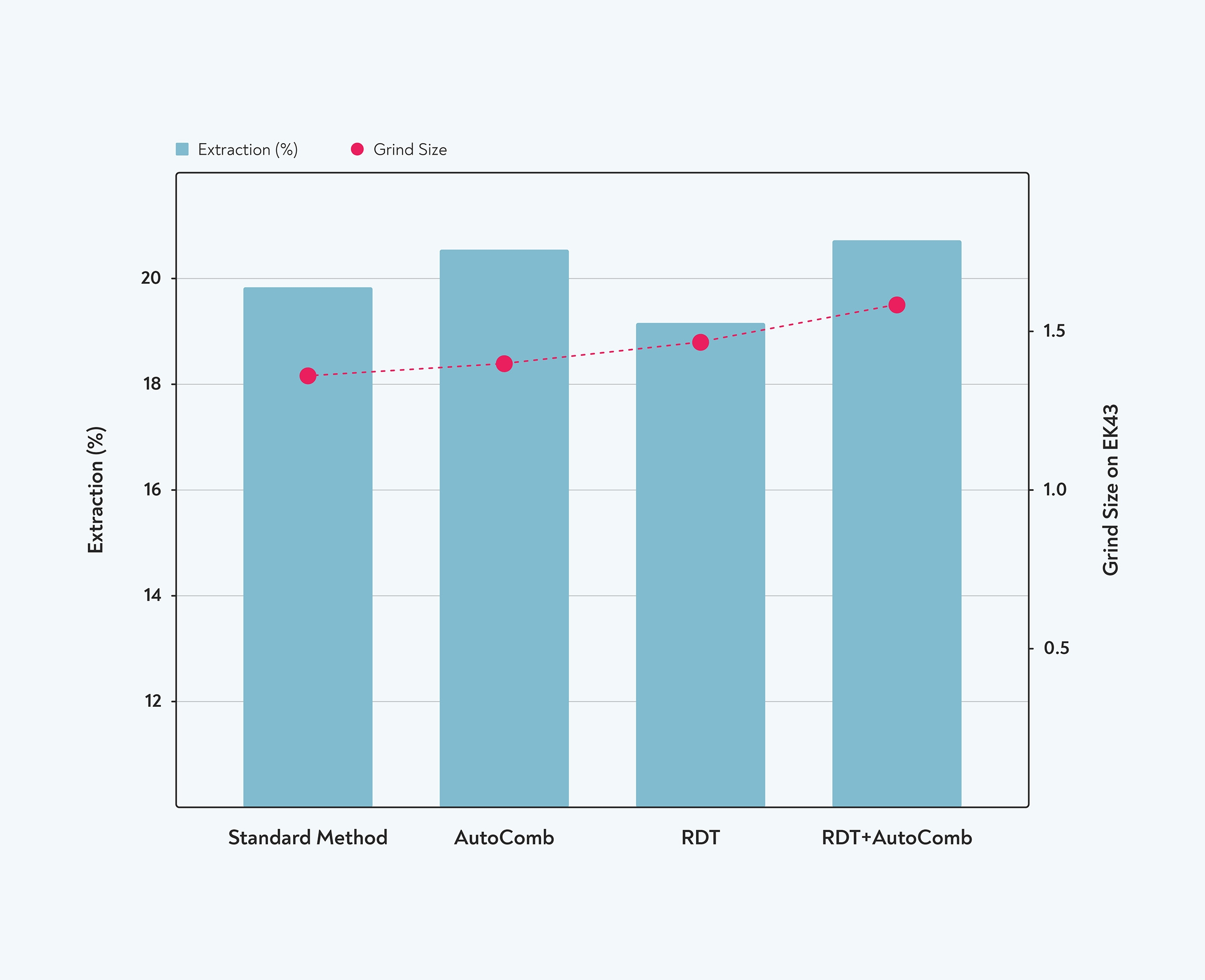

Working with regular BH contributor Lloyd Meadows, from Tortoise Espresso in Castlemaine, we set up some experiments to see how using the RDT, the AutoComb, or both together, affected the extraction in an espresso. We used a standardised technique to make all the shots, using an EK43 with TiN-coated burrs and a Linea Classic. Unlike Hendon’s team, however, instead of using a fixed grind size, we attempted to use a fixed shot time, dialling in to get as close as possible to a 25 second shot with each method.

To our surprise, we couldn’t replicate the effects that Hendon’s team saw. Adding 2% water did seem to slow the shots down very slightly, so we needed to use a grind size that was on average one notch coarser on the EK43. We did also get less retention in the grinder — about 0.1g per shot on average, compared to 0.2–0.3g with dry coffee. However, rather than increase extraction, the RDT reduced it — the exact opposite of the scientists’ results. Even in shots that were made using the same grind size, the extraction from the spritzed coffee was lower.

With the AutoComb, on the other hand, the extraction went up — and whether the grounds were sprayed with water or not seemed to make little difference. In fact, using both techniques together needed the coarsest grind setting to hit our target shot time, and produced the highest extraction of all.

Adding 2% water decreased extraction in our tests. On the other hand, using the AutoComb, with or without added water, increased extraction — even though it required a coarser grind to reach the same shot time.

Adding 2% water decreased extraction in our tests. On the other hand, using the AutoComb, with or without added water, increased extraction — even though it required a coarser grind to reach the same shot time.

Just in case the effect of RDT was dependent on shot time, we tried a few slower shots, and found that the extraction was reduced even further.

Of course, we don’t have the same volume of data, nor the high-precision equipment, that a laboratory does, so we can’t be quite as confident about the statistical validity of our results. But James Hoffmann, in his video about this research, also found mixed results. In his case, he didn’t report on extraction, but did note that whether or not spritzing the beans reduced the shot time seemed to depend on what type of grinder he was using.

The different results could depend on the materials used in the grinder or, he speculated, on the way that the grinder works. To find out which, he had the smart idea of helping his viewers to help him build a much larger dataset, covering a multitude of grinders and roast styles. If you’re able, we encourage you to try it out for yourself and share your data with him here.

We, however, were using an EK43 — the same grinder used by the researchers, so we might have expected similar results. One possible reason for the difference lies in the coffee we were using. How much static the coffee generates depends on its roast colour, or more accurately, on how much moisture is left in the coffee after roasting. Darker roasts have a lower moisture content and generate stronger negative charges. Light roasts tend to generate positive charge, while somewhere in the middle lie some coffees that produce very little charge at all.

Dark roasts (blue) generate negative charge on grinding, while lighter roasts (red) generate positive charge. Adding up to 2% by weight of water reduces the amount of charge generated in both light and dark roasts. Some roasts generate little charge, even without water added. Adapted from Harper et al (2023).

Dark roasts (blue) generate negative charge on grinding, while lighter roasts (red) generate positive charge. Adding up to 2% by weight of water reduces the amount of charge generated in both light and dark roasts. Some roasts generate little charge, even without water added. Adapted from Harper et al (2023).

Starbucks’s ‘Blonde’ roast, for example, has a water content of about 1.3% and generates a lot of static. The coffee that the researchers tested, Boneshaker from Reverie Roasters, is slightly lighter (Agtron 67) than Starbucks Blonde (Agtron 65), but considerably darker than James Hoffman’s own Red Brick espresso blend (Agtron 77).

The coffee we used, from Code Black, was similar in roast colour to Red Brick, and so presumably produces a lot less static in the first place than the darker roast does. This alone could be enough to explain why we didn’t see any benefit from the RDT.

Two Pathways to Higher Extraction

After trying both methods side by side and getting such different results, it seems most likely that the AutoComb and the RDT are working in substantially different ways. Perhaps the RDT is most effective at breaking up the kind of small, 1–2 mm aggregates mentioned in the paper — while the AutoComb is targeting larger clumps and thereby evening out the overall macrostructure of the coffee bed?

The fact that RDT didn’t work well for us doesn’t mean it won’t work for others, of course. Depending on your roast, your grinder, and perhaps other factors we don’t yet know about, you may still find that it’s a technique worth experimenting with. And even if it doesn’t boost your extraction, less retention and a cleaner workspace are a great bonus. (Note that if you’re using RDT and trying to calculate the extraction, you’ll need to account for the extra water in the grinds).

But whatever effect the RDT does have, even at its best it certainly doesn’t mean that baristas no longer have to worry about distribution. If the RDT does work for you and increases your extraction, we are pretty sure that good distribution techniques (like the AutoComb, or even regular WDT tools) can still boost your extraction even further. And if the RDT doesn’t increase your extraction, but you still like to use it for its other benefits, then a good distribution tool is a must if you want a juicy, even extraction.

Revolutionizing Your Coffee Game: The Science Behind the Ross Droplet Technique

Hey there, coffee lovers! If you’ve been keeping up with the latest buzz in the java world, you might have heard about a nifty little trick that’s been brewing up a storm. It’s all about giving your coffee beans a quick spritz of water before grinding them. Sounds simple, right? But trust me, this tiny tweak could make a world of difference to your morning cuppa.

Why Spritz Your Beans?

Well, it turns out that this little trick can reduce the amount of static created while grinding your beans. And less static means less chaff sticking to every surface and fewer clumps in your grinds. According to some smart folks who’ve studied this, it can even boost the extraction in your espresso — but it seems to depend on your coffee and maybe even on your grinder.

You see, static makes coffee stick to grinders and form clumps. The finer the grind, the more static is created. So if you’re like me and love a finely ground brew, this could be just what you need!

The Science Behind It

This new research comes from a team led by Christopher Hendon (a computational chemist who also introduced us to freezing our coffee beans) and some volcanologists – yes, people who study volcanoes! They found some interesting parallels between how static works in volcanic eruptions and how coffee creates static during grinding.

The trick of spraying water on coffee before grinding it is generally called the ‘Ross Droplet Technique’ (RDT), named after David Ross who supposedly originated the idea back in 2005. For many years though, this technique was mainly popular with home baristas but rarely seen on bar.

But times have changed, my friends. As single-dose grinding has become more popular, and baristas have used esoteric methods to chase higher and higher extractions, techniques like the RDT are suddenly everywhere.

How Does It Work?

What Hendon discovered is that the static generated during grinding isn’t uniform. Some coffees generate more static than others, and particles may be positively charged, negatively charged, or even a mix of both. Darker roasts tend to generate stronger negative charges — and fines in particular seem to pick up more negative charge. On the other hand, lighter roasts and larger particles of any roast style are more likely to be positively charged.

The static causes the negatively charged fines to stick to larger particles, creating small (1–2mm) clumps that act as single large particles. These clumps reduce the surface area of the coffee available to the water and create uneven flow through the coffee bed, reducing extraction.

But here’s where it gets interesting: adding water neutralises static and prevents these small clumps from forming. To get the biggest reduction in static charge, you need to add up to 2% of the weight of the coffee in water — much more than just a single spritz!

The AutoComb Experiment

We decided to put this theory to test using an AutoComb – a tool designed specifically for breaking up clumps. We set up some experiments comparing RDT with AutoComb on an espresso extraction process.

To our surprise though, we couldn’t replicate Hendon’s results exactly. Adding 2% water did slow down our shots slightly but instead of increasing extraction like Hendon’s team found out; it reduced it for us! However with AutoComb we saw an increase in extraction regardless if we sprayed the beans with water or not.

So, what gives? Well, it could be due to a variety of factors. The type of coffee used, the grinder, even the moisture content after roasting can all play a part in how much static is generated. Darker roasts generate stronger negative charges while lighter ones tend to generate positive charge.

Two Ways to Better Extraction

After trying both methods side by side and getting different results, it seems that AutoComb and RDT work in substantially different ways. Perhaps RDT is most effective at breaking up small 1–2 mm aggregates while AutoComb targets larger clumps?

The fact that RDT didn’t work well for us doesn’t mean it won’t work for you. Depending on your roast, your grinder, and perhaps other factors we don’t yet know about, you may still find that it’s a technique worth experimenting with. And even if it doesn’t boost your extraction, less retention and a cleaner workspace are great bonuses.

But whatever effect the RDT does have, good distribution techniques (like AutoComb) can still boost your extraction even further. So why not give both a shot? After all, there’s always room for improvement when it comes to brewing the perfect cup of joe!

You must be logged in to post a comment.